The Man on the Chessboard

Gaining the world leaves no fewer holes than having gained none of it.

“He understands everything, and everything does not seem worth understanding. His cosmos may be complete in every rivet and cog-wheel, but still his cosmos is smaller than our world. Somehow his scheme, like the lucid scheme of the madman, seems unconscious of the alien energies and the large indifference of the earth; it is not thinking of the real things of the earth, of fighting peoples or proud mothers, or first love or fear upon the sea. The earth is so very large, and the cosmos is so very small. The cosmos is about the smallest hole that a man can hide his head in.”

— G. K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

We are peculiar creatures. Our minds and bodies are both our allies and our enemies. Sometimes they work together for our benefit and at times they battle over who will get to rule over us. What the mind dictates the body may disobey; the body’s desires the mind may condemn. What are we, then, exactly? Which of the two is superior? And do we ally ourselves with pure instinct and follow the directions of the body, or do we engage with reason and ally with the mind? Well, neither. We seem to be in the middle, or “above”, if you like. Our decision making processes (which the mind ultimately evaluates and carries through) may reside in the brain, and our actions may depend on the body’s cooperation, but neither of the two is fully us. Here I will try not speak of the soul - for this opens a completely different can worms - but I will speak about free will and how determinism ultimately kills joy.

In everyday life a man constantly makes choices that shape his future. He can choose (or not) to greet an old friend he sees crossing the street; he may choose to smile at the cashier and ask her how her day is going, choose to stay up late and cancel his early morning appointments, say thank you or nod instead, swear at the driver who just cut him off, pray for the rageful idiot who suffers in his pride, treat people with kindness over bitterness. He may choose among a million different things. I would go as far as to argue that he can even choose his own beliefs. The point is though that, for a sane man, free will is undeniable and no amount deterministic gibberish can convince his friend who just got smacked in the face by his needless insults. We know this, but does he?

Granted among these million different things there can be some that don’t seem to be a matter of choice. For him everything has a cause, apparent or hidden. Even the childish act of humming a nice tune, smelling a rose, using a stick for a sword, or touching grass. The big questions ultimately sway him towards the maniacal search for understanding. After all, how can he choose joy over sadness? How to ignore what strangers think of him? How to control his anger? How to overcome nostalgia and despair? How to believe in God?1 These things seem predetermined and inescapable through our blurred vision of the world. His fatal conclusion is the rejection of even the most innocent causelessness. And with it he brings the death of wonder.

A great mystery the determinist has to grapple with is the mystery of doubt. How can doubt exist in a deterministic universe? Why do we stress about our choices if there is no choice at all? What kind of cosmic joke makes us doubt of what we are wired to do? In more plain words, what is the cause of doubt given the supposition that choice is predetermined and therefore there shouldn’t be any doubt? Of course, for the free will absolutist, doubt is (perhaps) like the reaction of the immune system when an intruder is detected. It signals that a current position in time and space causes a painful internal disharmony between mind and body which urgently gets transferred “above” for immediate inspection, i.e. we made a wrong choice and now we have to suffer the consequences2. Now the genius determinist might say: “aha! you grant that there is a proper choice. Surely this must mean the right choice is predetermined, hence determinism must be true.” But this does not negate the fact that I still made the wrong choice. Ignoring for the sake of argument whether a proper choice exists for every circumstance, if determinism is true then I shouldn’t have made the wrong choice at all!

I digress.

Returning to our man in question - a man who rejects free will but is tormented by doubts, as all men have been at some point - he now sits at his workspace, ignoring the quiet grumbling of his immaterial conscience, and begins the arduous process of fortification and immunization. He journals, sets goals, reads books, exercises, plans his future, invests; he buries himself in his study and thinks nothing except how to get what he wants. He dreams of a new life, harmonious and predictable. No more approval-seeking, no more useless sentimentalities, no more mystery. Utilitarianism in all its glory. His dream world is a perfect map, pointing exactly at the treasures and the dangers, the right paths and the traps. Perhaps he seeks the perfect philosophy that can be applied anywhere, or such an understanding that will make all predictions valid. But what is there to keep him sane if all is fate? When all is planned and all is determined, what good is it to randomly experience life? In this worldview we, as products of the millions of processes of soulless matter, have no other choice. The limitations of this philosophy breed insanity. What is excluded - simple things that a normal human being values - has to be done so forcefully.

Ultimately, his aim is false. His orientation is skewed. His compass points to an infinitely dense forest, impossible to navigate through. The life he dreams will never come, not in this world. What this man does not understand is the absurdity of his situation. In his quest for harmony he attempted to absorb the world and, in a calculated and logical manner, become one with it through understanding and adaptation. Like a passionate logician he attempted to iron out the wrinkles in the fabric of life. In the end he marveled at his achievement: a world of habits, mantras, strict routines and perfect responses; an infinite chessboard. Determinism and materialism shake hands.3

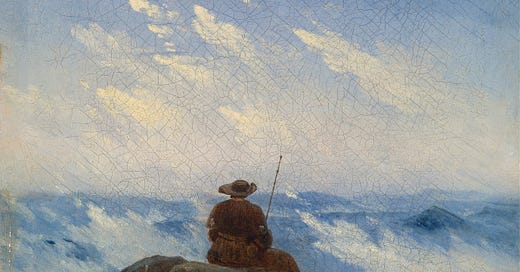

Now suppose that, out of the vast chaos of the cosmos, a strangely iridescent sphere were to appear in the center of this barren sterilized geometric landscape. An anomaly like this might perhaps manifest itself through profound events like serious sickness, religious experience, death, the birth of a child; or through terribly ordinary experiences like the smell of the summer breeze, the hues in the sky as the sun sets in the ocean, his mother’s laughter, how the golden sun beams are reflected on a sea of crystalized snow, reading a mere children’s book. To the sane person these are anything but anomalies. This is what life is all about; experiences that extend infinitely to the realm of the spiritual; a realm much larger than the infinite prison of materialism.4 The sad joy accompanied with such experiences is at the heart of the poet, the artist, the romantic, the believer. These people will never go insane as long as they rely on wonder and imagination. Thus it is the opposite of cold habit and frantic predictability that brings true harmony: it is a life of acceptance and expansion.

“To accept everything is an exercise, to understand everything a strain. The poet only desires exaltation and expansion, a world to stretch himself in. The poet only asks to get his head into the heavens. It is the logician who seeks to get the heavens into his head. And it is his head that splits.”

— G. K. Chesterton, Orthodoxy

What Chesterton describes is the perfectly reasonable madman. He has figured everything out, albeit in an imperfect manner, but remains a madman nonetheless. This is precisely the dreamer of our story. And it is his dream that crumbles. He will never fully accept the world, so he tries to reduce it. The more he understands how things work, the weaker his ability to look past mere things. Gaining the world leaves no fewer holes than having gained none of it.

Man rejects the material universe. We long for myth and mysticism, art and poetry, nature and music. These are wild forces that will never be caged. To be sane is to welcome them; to welcome mystery and be in love with it. To find meaning is to embrace causelessness.

The known assertion that one cannot force himself to believe in the things he does not believe in.

Or there is something much more fundamental that I’m missing here.

To quote Chesterton once more:

The determinist makes the theory of causation quite clear, and then finds that he cannot say “if you please” to the housemaid.

For infinities definitely come in all sizes.

You are doing amazing work. This is very very good stuff, and mirrors and distills many of my own thoughts on free will and predestination.

If you've not read Marilynne Robinson's 'Reading Genesis', then I think you'd enjoy it. She grapples with the thorny issue of determinism and free will very well.

I very much enjoyed this piece, John, and your selected quotes by Chesterton were spot on!

Your thoughts on the “infinite prison of materialism” reminds me of C.S. Lewis’s essay, “Imagination and Thought in the Middle Ages.” He writes, “You can lose yourself in infinity; there is indeed nothing else much you can do with it. It arouses questions…But it answers no questions; necessarily shapeless and trackless, patient of no absolute order or direction, it leads, after a little, to boredom or despair or (often) the haunting conviction that it must be an illusion.”