The Philosophy of Cosmicism: Humanity's Insignificance in the Face of Cosmic Truth

A Howard Phillips Lovecraft Tribute - Part 2

The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.

- H.P. Lovecraft, Supernatural Horror in Literature, 1927

Howard Phillips Lovecraft was born on August 20, 1890, in Providence, Rhode Island. His entire life was scarred by sickness and depression. He struggled to reconcile his passion for writing fiction, his obsession with the past, and the call to venture beyond human imagination into the unexplored reaches of the cosmos. Before he could manage to do so, he died penniless and almost certain that his works would never achieve fame. But he was wrong. His fiction spawned a whole universe of entities, locations, and characters; the widely known Cthulhu Mythos. His tales of eldritch forces operating on the minds of war-torn mankind from the endless abysms of space weren’t written simply for entertainment. They cast a bright light into the very soul of the human species and explore the feelings of awe, dread, and sheer horror we experience when we contemplate our place among the stars. The beautiful and seductive incapacitation one experiences when considering the vast expanses of space above our heads is brilliantly reproduced again and again in Lovecraft’s tales. He has earned his place in the pantheon of the greatest authors of fiction to have ever lived and his dark philosophy of Cosmicism has generated unparalleled tales of cosmic horror and wonder.

The Origins of Cosmic Horror

At some point in our lives, we become aware of our insignificance in the cosmic scale. The time and place of this sudden realisation certainly depends on the person, but it tends to go unnoticed how deeply ingrained such a feeling is in our psyche. How else would we explain the instinctive shivering when the cool air of the night hits the back of our necks? Why are we all afraid of the dark? What does life's subconscious, having evolved for millions of years, detect that causes such a stimulus in the amygdala? Us enlightened and scientifically developed beings shouldn't give much notice to superstition, should we? Well, we do and we don't know why.

Despite our inventions, our cultural progress, and the historically extreme prolongation of our lifespans, primal fear remains inescapable. It always existed and always evolved. In the beginning it was expressed towards the unknown governing principle behind nature's forces. Extreme weather conditions and horrifying changes in the landscape caused by earthquakes and volcanic activity were the source of early humanity's nightmares. As time went on, more sophisticated societies gave this principle a name: God. He is an existence beyond the known realms of space and time who governs people's fate in life and in death. Every event in life was considered "God-given" and it was either a blessing or a curse depending on how virtuous the subject of the event was. Archaic mythologies consisted of anthropomorphic deities with unimaginable power and the ability to exert influence on every aspect of daily life.

As the centuries went on, with the advent of Christianity, repentance was practiced to such an extent as to cleanse one's soul from sin and, by gaining the favour of the cosmic order (echoes to Buddhism), grant passage to a peaceful afterlife. Still, fear persisted. It changed forms from unexplained natural phenomena to supernatural phenomena. The latter were culturally depicted in classic horror stories of ghosts, haunted mansions, abandoned gothic castles, vampires, vengeful spirits, and other literary cliches. The breaking of the norms was, and still is, a constant source of terror - an instinctive reaction to the displacement of order with chaos and uncertainty. Finally, in the most recent century, a secular and enlightened approach based on logic threw away the superstitions of the past and pridefully declared the world safe from supernatural horror; from now on, the only issue plaguing humanity would be the nature of morality.

To no one's surprise, fear persisted once more. The thirst for horror stories did not decline any more than the fear of the dark vanished when some scientific committee deemed it irrational. The evolution of science, especially in the areas of math and physics, allowed the most sensitive of scholars to articulate this fundamental fear of all fears; the fear of the unknown. Lovecraft was one of those writers - preceded by brilliant artists such as Edgar Allan Poe, Arthur Machen and Lord Dunsany, and succeeded by Clark Ashton Smith, August Derleth and many other contemporaries explicitly mentioned and praised by Lovecraft in his essays and letters - who were able to unearth the ultimate form of cosmic horror and reproduce it in their brilliant tales of terror whose effect resembles an unholy warning on how unimpeded scientific discovery can bring about a crisis in meaning and its potential annihilation. The vast expanses of the universe which no man can ever hope to fathom, let alone begin to traverse, opened the bag of Aeolus and released the cosmic winds of terror and meaninglessness.

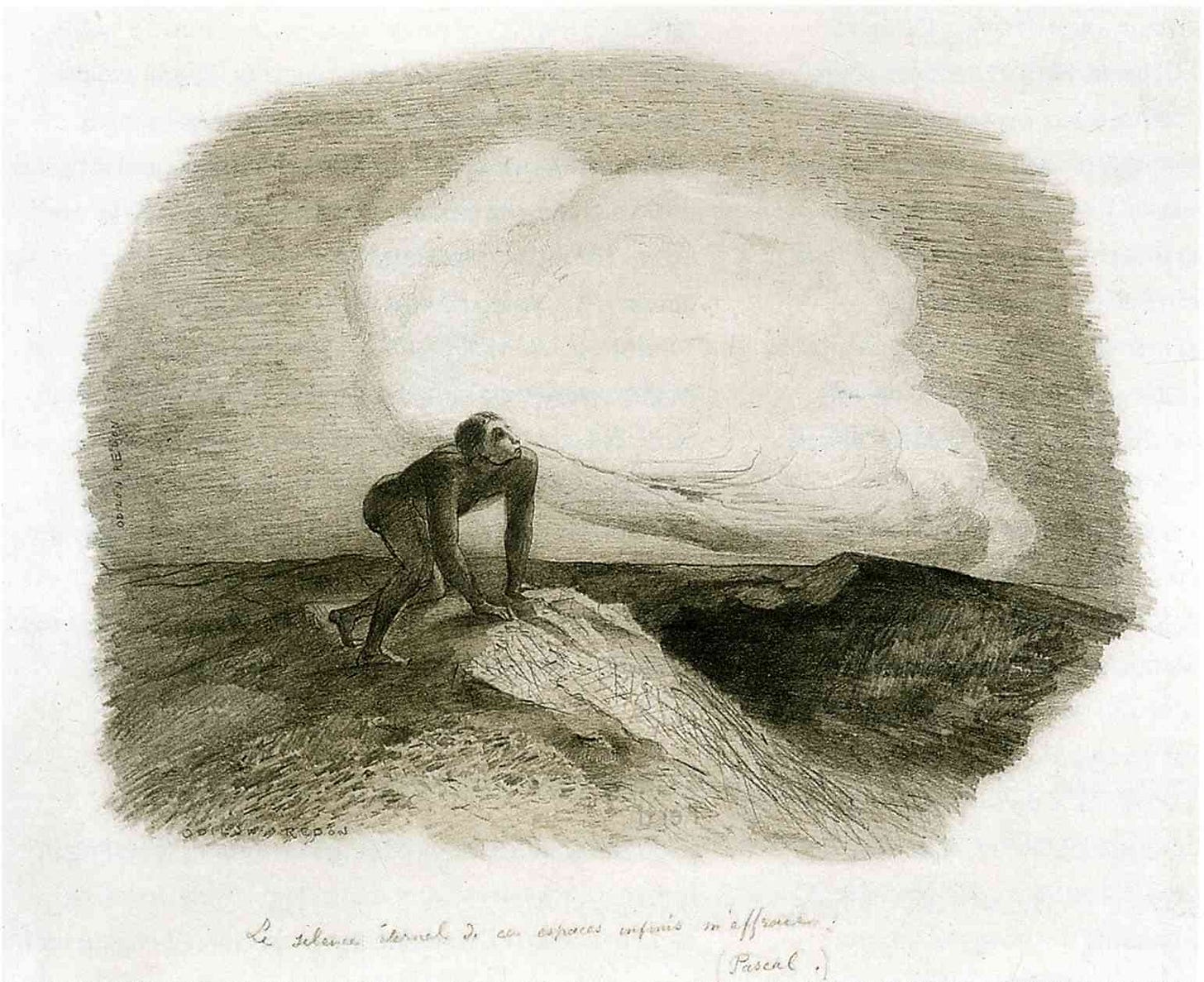

The eternal silence of these infinite spaces scares me.

- Blaise Pascal

In Supernatural Horror in Literature, Lovecraft brilliantly describes the biological and evolutionary origins of fear, some of which I touched on in the preceding lines. What is extremely haunting is the verbing and descriptions of that fear; he speaks of the vast gulfs of the Cosmos that exist outside of space and time, where multidimensional beings reside beyond the human capacity for thought, as an undeniable fact tied with an infinite Universe - and infinite it is for us cosmic quarks floating on the surface of a sphere barely the size of an atomic nucleus compared to the surrounding blackness of the Universe. What characterises cosmic fear is the vagueness of it; it is something that you cannot quite explain and at the same time it is profoundly existential. It is the threat of having the rug of reality pulled violently under your feet when a sudden whisper in a dark forest triggers the fight-or-flight mechanisms in the brain. The fear of slyly hidden existences residing in the far reaches of the Universe - now obviously deducible by the sanity-crippling discoveries in the field of physics and astronomy- is what governed the psychology of the human species for millennia. He writes in the introduction of this essay:

. . . The sensitive are always with us, and sometimes a curious streak of fancy invades an obscure corner of the very hardest head; so that no amount of rationalisation, reform, or Freudian analysis can quite annul the thrill of the chimney-corner whisper or the lonely wood. There is here involved a psychological pattern or tradition as real and as deeply grounded in mental experience as any other pattern or tradition of mankind; coeval with the religious feeling and closely related to many aspects of it, and too much a part of our inmost biological heritage to lose keen potency over a very important, though not numerically great, minority of our species.

He continues:

. . . Uncertainty and danger are always closely allied; thus making any kind of an unknown world a world of peril and evil possibilities. When to this sense of fear and evil the inevitable fascination of wonder and curiosity is superadded, there is born a composite body of keen emotion and imaginative provocation whose vitality must of necessity endure as long as the human race itself.

An infinite Universe stares us in the face every time we look at the starry night sky. We do not know what we are looking at, but we also do not know what is looking back through us. The implications of such a revelation can be disastrous, in some cases even physically painful. Sanity will exist no more and, as with many tragic protagonists in Lovecraft's stories, death will come as a mercy; anything that brings back the blissful ignorance so carefully provided by science which, although subject to technological and biological limitations, soothes the intuitive soul of the cosmically unimaginative. After all “such things do not exist”, we murmur incessantly in feverish nightmares believing ourselves to be all-knowingly rational and reasonable.

The Philosophy of Cosmicism

There will always be those among us sensitive enough whose curiosity will prevent the total retreat to oblivion. Lovecraft writes, in At the Mountains of Madness (1931):

There are those who will say [we] were utterly mad not to flee for our lives after that; since our conclusions were now—notwithstanding their wildness—completely fixed, and of a nature I need not even mention to those who have read my account as far as this. Perhaps we were mad—for have I not said those horrible peaks were mountains of madness? But I think I can detect something of the same spirit—albeit in a less extreme form—in the men who stalk deadly beasts through African jungles to photograph them or study their habits. Half-paralyzed with terror though we were, there was nevertheless fanned within us a blazing flame of awe and curiosity which triumphed in the end.

It is plainly obvious that scientific inquiry is unstoppable. Tracing this statement to its terrible conclusion, we read in The Call of Cthulhu (1926):

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

The ultimate form of cosmic horror is that which is unexplained and unexplainable, and the literary genius of H.P. Lovecraft stops the reader dead in his tracks and forces him to question his own sanity. The stirring interplay between the curse of the thrill of exploration and the inevitability of terrible discoveries that lead to the frantic desire of forgetfulness, are themes to be found in Lovecraft's works and introduce the reader to the philosophy of Cosmicism1 - a philosophy whose essence is our own cosmic insignificance. Overwhelmed by the blackness of this new reality, we slowly lose sanity as blasphemous correlations begin to manifest themselves in the unconscious.

A brilliant example is the early tale Dagon (1917) where an unlucky castaway stumbles upon an otherworldly monolith in the mysteriously risen sea-bed. Overcome by the horror of its possible meanings and submerged in the consequent reality, he decides that oblivion is the only salvation to insanity - by any means necessary. Another case where exploration goes horribly wrong is The Shadow Out of Time (1934), one of Lovecraft's last masterful attempts to capture that age-old feeling of desolate helplessness. In this novella a group of scientists visit the vast deserts of Western Australia when the discovery of a sandy plateau of ruins brutally crushes any preconceived notions about the nature of reality. Here, similar to At The Mountains of Madness (1931), Lovecraft describes in scientific prowess and eerie detail the discovery of an ancient civilization whose origins predate all the known geological periods of our planet. Both tales are masterfully connected with each other and take the reader on a journey inside the cyclopean masonry of a long forgotten civilization where the prospect of unleashing monstrous cosmic forces haunts the protagonists' every move.

As to what is meant by "weird" - and of course weirdness is by no means confined to horror - I should say that the real criterion is a strong impression of the suspension of natural laws or the presence of unseen worlds or forces close at hand.

- Letter to Wilfred Blanch Talman, August 24, 1926

Materialistic and atheistic from his younger years, Lovecraft strongly asserted his belief that the idea of the existence of a personal God who cares for mankind's struggles is utterly ridiculous. His ultimate creation, the Cthulhu Mythos, is a pantheon of entities resembling ancient mythological creatures as well as products of a horrific miscegenation between men and cosmic entities. His critics would often mention this contradiction in his work: he denies religion but simultaneously creates a pantheon of otherworldly beings acting as gods. However, if one devotes an ounce of effort in studying his works it would become obvious that this contradiction is precisely what elevates him above his predecessors and successors. These beings do not conform to humanity's ideals; to us they are evil simply because their existence is governed by laws that are impossible to understand and decipher. Indifference is misinterpreted as evil. How then does an indifferent universe support the existence of God? For Lovecraft, this is the truth of an infinite universe and its denizens, and when one finally accepts it then religious dogma will crumble.

This sentiment is strongly elaborated in most of Lovecraft's works. Poisonous entities consume the earthly environment and slowly transform all life - as depicted in the atmospheric The Colour Out of Space (1927) - before vanishing never to be seen again except as a horrific memory of the now insane witnesses. Others work as leaders of alien cults, like the Great Cthulhu from The Call of Cthulhu (1926), whose followers mindlessly attempt his return and orchestrate his rule over all life. In the same category fits the many-faced god, Nyarlathotep (1920). Arguably Lovecraft's most interesting creation, Nyarlathotep torments humanity simple for his own pleasure, or so it seems to us humans who couldn't possibly begin to fathom his true intentions. In his tale of the same name, Lovecraft describes Nyarlathotep as the crawling chaos - a shadow which causes unrest to the masses that blindly follow him until their inevitable demise as they enter the cosmic planes where he alone resides. Other creations feature the inbred inhabitants of secluded Innsmouth - in The Shadow Over Innsmouth (1931) Lovecraft explores their affiliation with the sea-god Dagon worshiped in the dark depths of the ocean. Some of his more elaborate world-building can be found in At the Mountains of Madness and at The Shadow Out of Time where beings such as the Elder Things, the Shoggoths, and the Great Race of Yith, are given a beautiful historical background in freakish detail.

Lovecraft's creations, worlds and entities alike, are imbued with the spirit of cosmic horror which will provide plenty of satisfaction to those sensitive readers who look for beautifully written science fiction and wish to come into contact with our primordial instincts, of whose the ultimate source is the fear of the unknown.

Children will always be afraid of the dark, and men with minds sensitive to hereditary impulse will always tremble at the thought of the hidden and fathomless worlds of strange life which may pulsate in the gulfs beyond the stars, or press hideously upon our own globe in unholy dimensions which only the dead and the moonstruck can glimpse.

- Supernatural Horror in Literature, 1927

Remembrance

Lovecraft was a man living in the past with a yearning for exploring the universe and the potentially infinite worlds therein. He had fully adopted Cosmicism as a way of life without falling in the trap of inaction so dangerously accompanying similar philosophies that deal with meaninglessness and nihilism. Believing that true art comes from the unfiltered expression of oneself on paper, his philosophy flows through his works unimpeded by the literary standards of his time.

His stance on mankind however, had always been one of cynicism:

With my basic cynicism and essential indifference to mankind and all human institutions I couldn't very well pose as Helpful Person with a Mission.2

It is the frank & cynical recognition of the inevitable limitations of people in general which makes me absolutely indifferent instead of actively hostile toward mankind. It can go to hell for all I care - but I'm not even interested enough to give it a push. It doesn't need me & I don't need it - its only use is to build quaint cities for me to enjoy a century or two later!3

Despite that, he never shied away from offering assistance to many up-and-coming artists and took up the job of reviewing and enhancing many unpublished drafts. His extremely sentimental character on matters of atmosphere, general aesthetic and natural beauty, would often cause him to daydream and weave his experiences in new stories.

Following the thread of his works - and mostly his letters - we exhale in relief to discover that however doomed mankind may be, an indifferent universe does not correspond to a universe without beauty. Magic exists and we need not look for it in the infinite gulfs of a dark, foreboding, and hostilely indifferent cosmos. It exists in the way the setting sun illuminates the fields turning green to gold and the fiery sky is mirrored in the river's still waters. Beauty can be found in the colourful garden at our backyards, in the seconds before sunrise, in the sweet birdsong early in the morning, in the smell of the ocean, the cool breeze atop the mountain, the city landscape backdropped with the golden sunrays of late afternoon slowly changing from day to night through a panorama of iridescent wonder - there is something profoundly eternal and nostalgic in the sensations that arise from such wondrous mirages.

It is as if we have seen it all before - somewhere, somewhen. The meaning of life when everything seems insignificant lies in the never-ending pursuit of this feeling of belonging. Because it is not a mere admiration of life's beauty; it is the profound realisation that infinity exists inside all life. We have a deep connection with this world and others long forgotten, now and in the distant past. Thus, the ethereal manifestation of reality's fabric causes a hypnotic attraction enhanced by instinctive awe and terror. Then and there, for a split second, all physical laws break down as we tread the boundaries of consciousness.

There is no more suitable way to conclude this tribute than citing a passage written by H. P. Lovecraft himself to one of his closest correspondents - the man partially responsible for his universal acclaim:

The vistas I relish most are those in which the sunset plays a transfiguring & glorifying part. Sometimes I stumble accidentally on rare combinations of slope, curved street-line, roofs & gables & chimneys, & accessory details of verdure & background, which in the magic of late afternoon assume a mystic majesty & exotic significance beyond the power of words to describe. Absolutely nothing else in life now has the power to move me so much; for in these momentary vistas there seem to open before me bewildering avenues to all the wonders & lovelinesses I have ever sought, & to all those gardens of eld whose memory trembles just beyond the rim of conscious recollection, yet close enough to lend to life all the significance it possesses. All that I live for is to capture some fragment of this hidden & just unreachable beauty; this beauty which is all of dream, yet which I feel I have known closely & revelled in through long aeons before my birth or the birth of this or any world. There is somewhere, my fancy fabulises, a marvellous city of ancient streets & hills & gardens & marble terraces, wherein I once lived happy eternities, & to which I must return if ever I am to have content. Its name & place I know not save as reason tells me it has neither name nor place nor any existence at all-but every now & then there flashes out some intimation of it in the travelled paths of men. Of this cryptic & glorious city-this primal & archaic place of splendour in Atlantis or Cockaigne or the Hesperides -many towns of earth hold vague & elusive symbols that peep furtively out at certain moments, only to disappear again. . .

- Letter to Donald Wandrei, Providence, April 21, 1927

I strongly recommend the YouTube channel Eternalised. They have produced two excellent video essays on Cosmicism and the place of Lovecraft’s philosophy among others such us Nihilism, Existentialism, etc.

Letter to Zealia Brown Reed (Bishop), Providence, February 13, 1928

Letter to Donald Wandrei, Providence, March 27, 1927

Thank you for this deep dive into Lovecraft's philosophy and literature. Lovecraft's ability to tap into our primal instincts and weave them into tales of cosmic horror is truly remarkable. It prompts reflection on our own place in the universe.